Home

Deidre Scherer

"This has really been a wild, wild year," says Deidre Scherer about a time of unprecedented fulfillment in her life.

For twenty years, this studio artist from Williamsville, Vermont has chosen fabric and thread as the medium to compose a series of compelling images. The subject matter is aging and the end of life -- portions of the life cycle few of us explore willingly, if we explore them at all. She finds her human models in nursing homes and hospices -- places our culture tends to shun and artists rarely witness.

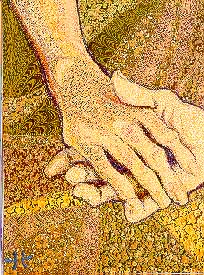

Even though she's drawn to concerns that seem almost taboo, Scherer's zigzag-stitched cloth renderings of elderly heads and hands have not only found an appreciative audience, they've also earned her widespread recognition. This is something she's intentional about; she estimates spending one-third of her time on publicity, entering competitions, and other business tasks related to her career as an artist. As a result, her work has appeared on seven book covers, including the best-seller, "When I am an Old Woman I Shall Wear Purple"; 25 of her fabric images illustrate the poems and essays in another Papier-Mache Press anthology, "Threads of Experience." Her work has been purchased for many private and institutional collections and included in more than 90 individual and group shows.

She has a long list of professional credits, but she's as

excited about what's happening currently as if success is a brand new experience. When on

March 11th the Baltimore Museum of Art opened her solo exhibition "Deidre Scherer:

The Threaded Image" in their new textile gallery, Scherer was positively elated.

"Yes! Just pinch me," she says gleefully about this peak achievement. "I

had been showing at the American Craft Council Fair in Baltimore for a number of years.

Seven years ago, the assistant to the curator in charge of textiles came through, and then

the curator herself. From that direct contact in my booth at the fair, we spoke about my

having an exhibit."

To promote the show, the museum hung a huge banner featuring Scherer's "Recognition", an evocative image of an elderly woman's head, on the columns at the building's entrance. For a period of time, this was flanked by a banner for an exhibit by the late pop artist Andy Warhol, then by a banner displaying Edvard Munch's famous painting, "Scream". "Ahhh, that's how I felt," says Scherer, referring to "Scream". "It was thrilling to see my name next to Warhol's and Munch's. It's one of those rare, rare, amazing things, and I wish it weren't as rare."

Then in June her book, "Deidre Scherer: Work in Fabric & Thread" was released by C & T Publishing. It's definitely another peak achievement. Dedicated to the memory of "my Nana, Constance Gillis Sampiere, and all grandmothers and wise women", the 144 pages of color photographs and carefully-written autobiographical text offer rich insights into Scherer's passionate creativity with cloth.

One chapter in the book shows the drawings of her real-life models alongside the sewn fabric images inspired by the drawings. "I actually draw the image three times," she explains. "The first time I draw with charcoal or graphite on paper. Then, I take that home and set it up in my studio where the fabric is."

Each drawing is in black and white, as are the photographs she sometimes takes of her subjects. "I prefer black and white as this gives me more information about the modeling of a face," she says. She then adds what she calls "different tiers of color." "I take a black and white drawing or photograph and dream on top of that structure all sorts of color impressions," she says.

In her studio, she studies the drawing as she cuts out the applique shapes freehand -- the second time she "draws" the image. "In essence, I draw with the scissors. I don't sketch it out onto fabric, I don't project it, I don't use a template. I get a thrill out of cutting directly into the fabric. I think of it as 'air guitar' -- cutting above the surface, then seeing how it fits and rests," she says.

This stage can take weeks or months of intense work all night long, her preferred time to create. "While I'm working on a piece, I will spend at least half the time gazing at it, looking at it, and seeing. Not pinning or cutting, but looking," she says. "It's a questioning, where you are getting with your eyes the next moves. That direction often comes right out of the cloth."

In "Harvest Hands", a spike of slate blue fabric gives the worn hands life. In "Legacy", several sepia-toned floral prints create shadows of leaves and vines which echo the wispy hair and brow line of the woman pictured. In "Envisage", swirling paisley prints and flowing tone-on-tone florals combine to form a lush tapestry portraying a seasoned mentor. "I use many layers of cloth," Scherer says. "I don't call it low relief, but it does have a lot of depth to it once it gets layered. As I'm building it, I think of it in sculptural terms."

She uses very fine pins to hold the fabric shapes together, gently stretching the layers to erase any puckers or wrinkles. Then draws the image once more, this third time with machine zigzag stitches. Scherer has two Pfaff #362 models and a programmable Pfaff-Creative #7570 in her attic studio. "I live by my machine," she asserts. It has become my right arm. I not only draw with my machine, I think with it."

Using various colors of standard cotton sewing thread, Scherer zigzags over the applique raw edges to blend or emphasize contours. Her stitching looks fluid, but it's not free motion work. "No, I don't drop the dogs. I adjust the machine for very light pressure on the presser foot so the fabric isn't squeezed. I like having that bit of friction to work with or against," she says. "That's just the way I've keyed into it."

Once the piece is complete, Scherer mounts it on a background such as muslin, monk's cloth or raw silk, then stretches this on foam core board. The background is as carefully crafted as the image and comments on the image. In "Crossings", a portrayal of the state of mind during Alzhiemer's disease, the mask-like fabric collage in the center continues into the torn, frayed, segmented border. In both "Poised" and "Saint", many threads have been removed to make a deep fringe edge on the background cloth; the fringe suggests energy, rays of light, or perhaps a halo surrounding the central image.

Scherer is careful to point out these are not portraits. "'Portrait' implies you accept doing commissions. I steer away from that. I call them 'heads, hands, and still lifes'," she says.

That may explain why the drawings which are created in the person's presence, are usually entitled with the name of that person such as "Gertrude", "Kenuth Johnson", or "M.F". In contrast, the fabric images are identified with descriptive words -- "Morning in December", "Sage", "Unsaid", "Unfolding". It's no secret that Scherer is trying to communicate essential information in a way that transcends the depiction of the real-life person.

"As the aging face has become my most significant subject matter," she writes, "it gives me particular joy to make the elders and the mentors more visible and accessible. Images of aging have the power to influence social change by aesthetically and psychologically challenging ageism."

Expanding on this thought during an early afternoon phone conversation (it seems like morning to her), Scherer says, "Great art is about death, and therefore, about life. There is something that crosses all kinds of religions, language barriers, and biases. I would hope that being visual does that. It would bring up anyone's questions about aging in their own style."

She believes using fabric and thread makes her images especially accessible. "There's something super exciting about textiles and the fact that we have it on our bodies all of our lives unlike oil paints or watercolors," she observes. "Our biggest organ of sense, our skin, can have its bells rung while we're viewing work made out of fabric."

The mini-print cotton fabrics she favors -- they're familiar quiltmaking fabrics for the most part -- are a key to Scherer's work. "I find that tiny flowers, leaves, and squiggles almost create the same kind of vibrations that the pointillists use when they're just putting color on canvas, " she says. "It moves. Our eyes will continue to read it and move it. We will reconstruct what's been given by the artist into, say, a full human hand. That activity makes the images especially exiting to me. You have more of an active looking."

Through her artistic use of fabrics and stitches, she is actually conducting a one-woman educational campaign. "I'm giving a chance to contemplate the bigness of life and miracle of life, and the idea of death and life. We don't have much room for that in this whole culture," she says. "There's a dearth of material about death and dying. I would encourage anyone who's inspired by these visions to look into their local hospice."

Scherer draws on her own hospice volunteer training to help her contemplate her private ideas and myths about aging as well as to enable her to connect so deeply with the nursing home and hospice clients who become her models. Hospice training also helps her handle the grief as she outlives them but continues to deal with their remembered presence as she works from the drawings she has made.

Scherer is active in hospice circles and considers her art as an act of hospice volunteering, so it's not surprising that she was honored for the advocacy aspect of her work by the International Congress for Caregivers of the Terminally Ill in 1994. She has been invited to exhibit her art and give a presentation on her work with the elderly at the 1998 Congress in Montreal -- adding yet another peak achievement to an already achievement-packed year.